I venture that there is nowhere in Prague with a more eclectic demographic than in Sherwood Forest, which is the nickname for the park and path system just outside of hlavní nádraží (Prague’s main train station). Businessmen and women storm off to meetings; students, tourists from all locales, and those escaping Prague for the day wander with bags.

I venture that there is nowhere in Prague with a more eclectic demographic than in Sherwood Forest, which is the nickname for the park and path system just outside of hlavní nádraží (Prague’s main train station). Businessmen and women storm off to meetings; students, tourists from all locales, and those escaping Prague for the day wander with bags.

Additionally, as suggested in the sobriquet, there is a certain element of the demi-monde present. Thuggish, tough-looking men and women strutting laps, those who find themselves monstrously and unapologetically intoxicated at 7 or 8 a.m., others who sleep off the night’s pleasures in the grass, the homeless, and those who are too mobile and alert to be homeless, but who nevertheless don’t look like a person who sleeps in a house.

Despite appearances, nobody really bothers anyone out of their little clique. I have been walking through Sherwood Forest every day for eight years and I have not been bothered once. But I am bothered today, by a person, but not directly. The woman who has been at the tram stop selling the Nový Prostor magazine every day is not there today and in her place is a man. And he looks right at me.

OK, let me just state for the record that I am for the most part a lucid man with a reasonably sound mind. I read about conspiracy theories occasionally, but mostly for entertainment. I believe that Bigfoot and Nessie exist. More to the point, I want them to exist. I like the mystery and fun of it. Like most reasonable people, I find Alex Jones certifiably insane and I would pay money to see Rush Limbaugh try to waddle his fat ass away from a hurricane contrived by liberals.

If you have ever taken a fiction class or a film class, or if you’re just a reader or film buff you have heard of the term the willing suspension of disbelief. The idea is that when you read a book or watch a movie, you willing put away your critical faculties and believe the unbelievable in the name of taking in a good story. And so we overlook implausible aspects of a story because we want to enjoy a story. Without our willing suspension of disbelief every Bond feat, every perfectly-timed home run and rescue, every Vin Deisel car chase, every time George Costanza got a date with a Ten, every John Wick fight, everything that happens in movies and books would be null and void.

Like most movie and book fans, I love it. I love letting myself get carried away by the improbable events in an entertaining book or movie. This willingness is essential in order to completely enjoy a narrative and there’s nothing like allowing yourself to do that. The payback is that a good horror movie can make everything in real life spectral, a good thriller makes everyone sinister, no matter how improbable its premise or events.

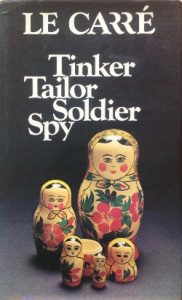

The last ten days I’ve been reading Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy by John LeCarre. This novel is about a Russian mole within the British secret intelligence service. It’s profoundly realistic in that there aren’t a lot of flashy Bondsian devices and gimmicks; there’s no flashy sex, no shock sparking car chases, and the only murders are in mentioned side stories and background.

Therein lies the problem: I don’t have to suspend my disbelief. The action takes place in such real life ways and such real life increments that there’s no reason to disbelieve it. The agents are low-key, quiet men and women going about their business. They could just as well be marketing executives talking about the Schooner Tuna account. The characters work in libraries, discuss things in offices, and talk in cars, meet at very real flats, and outside on park benches. Nobody has a super power for spying. They are well-trained and well-educated operatives, they pose as food vendors and sports columnists. The car washer turns out to be a polylingual agent undercover in this role for nine months. The spy can be anyone from the doughy old secretary, the pizza man, or the lawyer at the bar.

Or maybe a (different) person selling a magazine on a tram stop near a park.

Thus, the paranoia.

My own too willing suspension of disbelief aside, this book is fantastic. Every detail is believable, every paragraph fills in pieces of the story via background, foreground, body language, and subtext beneath dialogue. LeCarre is a master storyteller, which he’d have to be to send such a cool-headed dude like me through a fit of paranoia.

In other news, if that magazine salesperson is still there tomorrow, I have to get a new job.