Before anosmia as a concept exploded around the world, before anosmia became a word in the average person’s lexicon, before anyone even knew what the hell it was, I was there.

My story, like so many others that should never be told, started in the bathroom. About twelve years ago in my Prague 6 flat, I was doing that thing in the bathroom for which people employ books and phones. I shut away the world for a few minutes and let my body slip into its intestinal yoga. I was relaxed.

Far less relaxed was my flatmate, who was so overwhelmed by my activity’s odiferous results that he broke the code of all past and present humanity by offering commentary through the door. Other than desiring to drive a brick into his brain, I suddenly realized that I could not smell anything. I tried. Nothing. I voiced this to him and he assured me, through teary eyes, that he was not wrong. I went into the kitchen and grabbed a can of coffee grounds. Bringing them to my nose, I inhaled deeply. Nothing. Nil. Not a hint.

Huh.

My adventure into anosmia had begun. As has yours, maybe.

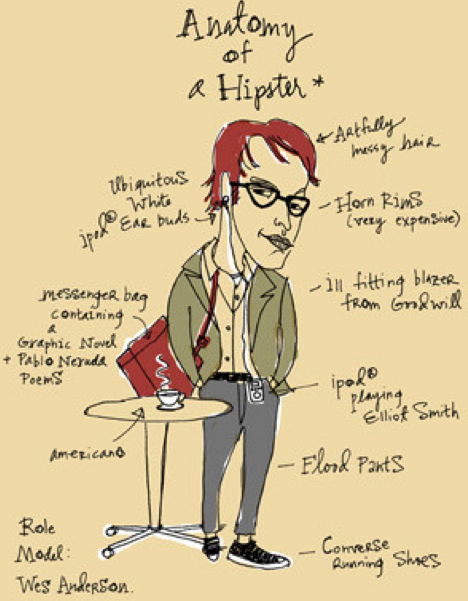

As you almost certainly know, one of the symptoms of contracting COVID-19 is anosmia – a loss of your sense of smell. I’ve read that it’s often how people first realize they have it. I’ve also read that if you are affected by this in the long term, you might not just lose your sense of smell, you might smell things unusually. A friend of mine hasn’t just lost her sense of taste and smell, but things like chocolate or spinach now smell like gasoline or as if they are burnt. That really sucks and I am sorry for that. I feel your pain, for I am the anosmiac hipster – I was there first, I was there before it was cool.

You’ll probably google “anosmia” and you’ll probably find some things you don’t want to find. The condition potentially leads to depression, lowered libido, and cardiovascular disease (because your taste also suffers and you season with salt more). Next, if you’re like me, you’ll google celebrities who have no sense of smell. Our club includes Bill Pullman, Jason Sudeikas, and Stevie Wonder, who, I realized with a churn, is down to three senses. That hardly seemed fair.

I first began telling friends shortly after realizing I had anosmia. Everyone I told found it weird and some found it funny. People hypothesized about my problem.

“Well,” said a colleague, “when people ask if you had to lose a sense, it would be smell.”

“Yeah,” I answered, “but if given the choice between being eaten by a shark or a crocodile I’d choose crocodile. It’s not like I wanted it to happen.”

Some just had – or have – trouble wrapping their heads around it all. “Really? Can’t smell anything? Here,” then they hold something under my nose, “Smell this.” Every time I see my brother he asks me to smell something. He’s not being a dick, he just doesn’t remember. I hope. I can’t remember him ever asking me to smell something before I lost my sense of smell, so punishment might have to be portioned out.

To be fair, it’s not a debilitating condition. People wouldn’t laugh at me if I was blind, my brother wouldn’t ask me to read something if I walked into his house with dark glasses and a cane. I suppose it’s weird and doesn’t overtly ruin one’s life, so it can be poked fun at. This is probably why I stopped telling people. There was no reason, they couldn’t help, and it only led to questions I’d answered dozens and dozens of times. If someone offered me something to smell, I’d lean my nose over it and inhale deeply and make the vaguest comment. But it had only been an air transaction. I went to my doctor.

“I think you’ll die of old age before we figure out what the result of this is.”

I was happy he didn’t freak out and summon a priest, but I was a little frustrated with his inertia. It did affect my life. So I went to another doctor who ordered an MRI. They found nothing wrong and sort of halfheartedly suggested a CAT scan. The prevailing attitude was: you can get on without it, so why go through the bother?

I don’t know, because I wanted to smell things? I went to a holistic doctor, who was also an MD. His office was on the river in a little part of Prague I never went to. We sat in his office for the first time. He spoke a little English and I spoke a little Czech and we got along like that. He told me to take off my shoes. He wielded a little electric pen wired to a meter and pressed it into my fingertips and toe tips. Each time he did, the meter registered and he read out a number in his gravelly voice and a disinterested nurse wrote something done.

“Your problem is in your stomach,” he said. “We do acupuncture.” He picked up a chart of the human body. “The final meridian of your nose is in your stomach.”

Ah, the stomach. The mysterious place that had its own special lore in my family. My stomach’s off, I had been hearing my dad say for thirty years. I sort of got it, but sort of didn’t. Could a stomach be so off that it knocked your nose off-kilter? I guess it was possible. So each week for six weeks I went to him and reclined in a long chair while he slid needles into my forearms, feet, and face. I don’t know what happened, sometimes the needles barely registered and other times it was as though he was sliding a katana in and out of my forearm or my ankle. When I winced to a particular needle, he’d notice and ask me something. “That one hurt? Are you having trouble sleeping? This other one hurt? Did you injure your leg? That one hurt? Did you get drink too much this weekend?”

The thing is, he was always right. I’d answer with a tentative yes. I didn’t get my sense of smell back, but my body did undergo a physical reaction. For the six weeks I saw that doctor, I took no fewer than ten shits a day. He was right about my stomach, but I had no idea where all of this material was coming from. In any event, I ended the experience with no sense of smell and was forced to face the fact that for the time being, this was life.

It took me a while to understand the other implications of anosmia on my daily life. Some were very real and pragmatic. Living with a gas stove can cause stress. If Burke says that something smells like it’s burning, I run to the kitchen where I inspect the oven and whatever food is in it for minutes. She is enlisted. “Does it still smell now? What about now?” When I’ve been alone, I have held the cat up to the stove to see if anything registers with her insanely sensitive eyes.

One of my enjoyments about daily life was fully removed. I could no longer smell wet leaves in the fall. I couldn’t smell the freshness of a spring day after a rain. I couldn’t enjoy those weird smells that are somehow good – skunks from a distance, gasoline, the damp gritty flavor of a row of street vendors. Pizza, tomato sauce slow cooking on a Sunday afternoon, a woman’s natural perfume. The list goes on and on and on.

One of the things I could no longer smell was myself. I live in Prague and I go to pubs with friends. But pubs in Prague are well known for their stench, as years of beer, smoke, and fried foods are contained within a room that rarely gets its windows opened. One morning I went to a class in a pair of pants I had worn the night before in a pub. The student made the international I-smell-something-bad face and we both looked for the source. When it became evident (to him, not me) that it was my pants, I was mortified. He was classy about it.

“You probably sat in something on the tram. Those seats are awful.”

I ended class early.

Personal hygiene and laundry became an obsession after that and have remained so. Everybody smells sometimes, they go for a run, skip a shower, or wear the same socks for a few days. But they know it. To this day, if I went to a bar, I wear all new clothes the next day. I shower every day, not putting on deodorant is not an option. In the last fifteen years, a prerequisite to living with me has been that the poor sap has to be my nose, my personal smeller. Lindsay Voight probably didn’t love being greeted at 7 am with a shirt or a pair of pants. Blinking sleepily, she’d sniff. “They’re fine.” Sean smelled things for me, but he was more vocally opposed.

“I don’t like this game. Nobody wins at this game.”

I do my part, though. I am a man with no nose. Send me in for cleanup duty. Need a toilet cleaned? I’m your offensive-less man. Stinky trash needs to be brought out? I’m the guy. You have a clogged sink? I am the man with no nose.

I think about all the jobs I can’t have. Should I decide on a whim that I wanted to be a detective, there’s a great chance my disability will get in the way. A doctor? Nope. A fireman? Nope. A chef, a sommelier, a baker? Nope. Nope. Nope.

They say when you lose a sense the others team up, become stronger, and balance you out. I have not noticed super bat-like hearing or the vision of a hawk. But I have noticed odd things, like the fact that visuals and sounds conjure hints of smell reminders. Walking in the local park last August, I looked up into the tall trees along the path just as someone was hammering something. It made a hollow, wooden sound. The combo of this sight and sound brought back a strong memory of boy scout camp when I was twelve. I was overwhelmed with it and I went home immediately to look up pictures of boy scouts in the 1980s (and no doubt ended up on an FBI list somewhere).

Pictures of Christmases past have conjured distinct scent memories of pine trees. And a glimpse of a swampy pizza shop can blast a little memory of the dense smell of pizza sauce and cheese and fountain sodas. It seems that though I can’t smell, my brain can remember how it was to smell.

In one year, the number of people on earth dealing with a loss of their sense of smell has skyrocketed. But let’s look at the bright side. This will almost certainly be an area of intensely focused study and, one hopes, medical advancements will come within the next few years. Let’s hope there will be new treatments and awareness of the issue will be raised around the globe. As an anosmiac hipster, I certainly do. And I better be first.