When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia from Boston, he was warned off of going to a tavern called “The Three Mariners.” Told it attracted a bad element, he was instead told of a place called “The Crooked Billet” which was far more reputable. It seems that Philly already had a bad reputation for ruffianism.

One of these people who warned him might have given him the hint: go away from the water. As taverns started popping up around the new colonies in America, they started at the water. This makes sense. Sailors and merchants coming from sea would want to wet their whistle and catch syphilis from a prostitute before heading back out to sea. And what better place to do those things than in a tavern. The further away from the water a tavern was, the more reputable the establishment and its clientele.

About 38 years before people were telling Franklin to stay away from coastal pubs, William Penn was consternated with the rowdy elements drawn to the taverns in the caves along the Delaware River. As most Philadelphia area residents know, not much has changed.

In the mid-1700s the Brits were noting the difference between beer drinkers and gin drinkers. As have drinkers for the last three hundred years. In 1751 in England, artist and social critic William Hogarth painted Gin Lane and Beer Street to point out the difference between the two lifestyles. Beer Street is full of mellow people admiring art, looking for a chip shop, perhaps a bit gassy, but otherwise just enjoying their day without ruining their lives and society. Gin Lane is rife with negligent parents, decay, suicide, wasted waifs of alcoholism, and what look to be some Disney characters.

What happened in England was happening in the colonies – Americans found hard alcohol. In England it was gin, in the colonies it was rum. Some travelers note that after a long day’s riding or rocking on a kidney machine of a wagon on harsh roads, rum might take the edge off, but it didn’t really quench a thirst. Imagine a long day of activity and then wetting your whistle with warm rum. But for its effects – boy did people love rum. This wasn’t necessarily the taste, but the fact that it got them where they wanted to be much faster.

Like Britain, America became a pretty drunk place. Taverns popped up all over the place. The fare was rum and some food to make you less drunk so you could drink more rum.

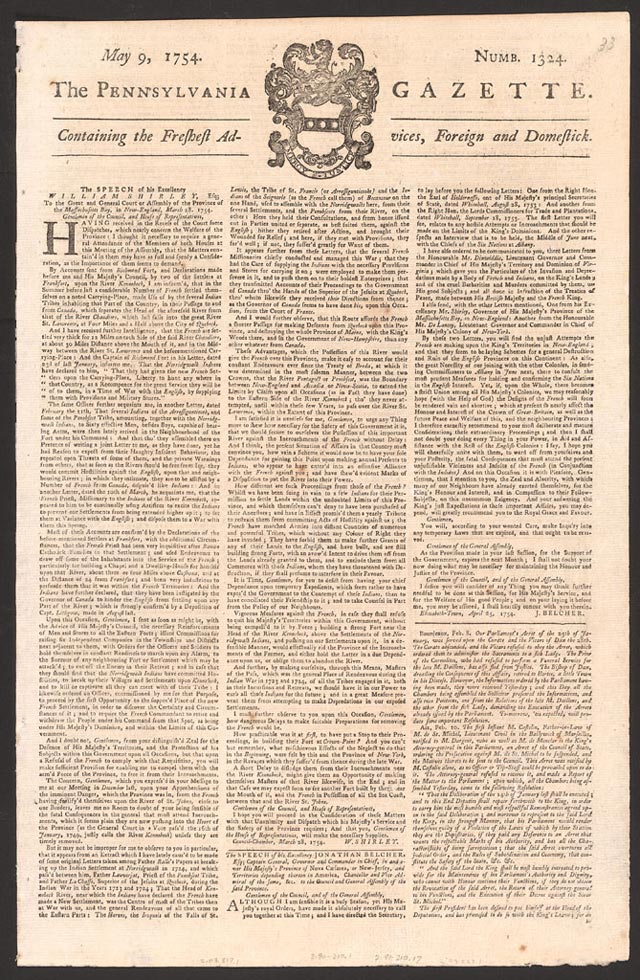

Perhaps in the same vein as Hogarth, Benjamin Franklin got in on the scene. Ben Franklin was not a teetotaler, but had rather found joy in the middle ground of moderation. He drank but did so for enjoyment rather than a sprint race to black out. He no doubt noticed what was happening around him in the taverns of Philadelphia. In 1737, he (or his middle aged widow persona Silence Dogood) wrote The Drinker’s Dictionary.

For many moons, people had been defining the effects of drinking. In 1592, Thomas Nashe came up with the 8 types of drunkards based on animals. These are ape, lion, swine, sheep(e), mawdlin (maudlin), martin, goat, and fox(e). Each step is supposed to represent what animal the man is supposed to resemble along the drunken journey. It’s not hard to imagine the first salves of drunkenness being related to an ape, nor the aggression of a lion, the maudlin weepy character that overtakes some later in the night (I love you, man!) and the horniness of a goat (Hey baaaaaaaabay, want some chicken…). It’s less hard to imagine the late stages of drunkenness being related to the crafty fox, but we can lend this to artistic license.

Franklin didn’t take his terminology from folklore (directly, anyway) but rather from the “modern conversation of tipplers” at local taverns. One (i.e. I) imagine him sitting in a corner of a pub, wearing bifocals, holding a kite, and perching pen above paper waiting for some drunks to start barking commentary at each other. He was evidently fond of rum punch, so I imagine him sipping a bowl of that while eavesdropping.

He is across the board with his terms. He goes religious: He’s going to Jerusalem; He’s been to Jericho; He’s as drunk as David’s son. He also talks about animals: he’s eat a toad and a half for breakfast. And then there is the straight up weird. He’s had a thump on his head with Sampson’s Jawbone; He’s halfway to Concord; He’s been with Sir John Goa; He’s been too free with Sir John Strawberry.

If we learn something from Franklin that we don’t from Hogarth, it’s a sneak peak into the undercurrent of pub culture and the language that grows from that. Who is Sir John Goa and was he created by an eastern Indian? Did He’s Halfway to Concord start out as an inside joke at one pub and simply bleed to the next door one and then the one next to that? Maybe David isn’t biblical as much as one of the patrons whose son couldn’t hold his rum punch. The ideas go on and on and on.

One wonders what Ben might have heard (and recorded) had he not been warned off the coastal taverns near the seaside. Those sailors must have hoisted some seriously colorful phraseology. The only more tragic loss to linguistics and etymology is the language of the 17th century cave taverns down by the Delaware.