As a kid, Halloween was simple and glorious. We drew witches and cats in school and made a macaroni ghost. We carved Jack O’Lanterns with plastic trowels. On October 31, I was put into a plastic mask, handed a pillow case, and told to walk around saying ‘Trick or Treat’ to strangers. For this simple task I was granted candy. This, I believed, was the world’s greatest scam. When I was older, I rued the ageist unfairness of it. I never considered the tradition I was taking part in.

Amid Halloween’s 2,000 year development and its many manifestations, it’s sometimes easy to forget that it all started with the ancient celebration of Samhain. For the Celts, a people who lived in Ireland, UK, and northern France from about 2,500 years ago, Samhain was one of the most important seasons of the year. It marked the harvest, the end of summer, and the beginning of winter. Most importantly to people who didn’t have electricity, it was the time ‘the light loses and the night wins’. There’s surely romance to the spookiness and the folklore of Halloween, we must remember that for the Celts it ushered in months of darkness, sparse food, and death.

To make matters worse, the Celts believed that at Samhain the barrier between their world and the ‘otherworld’ was at its thinnest. Thus, their deceased ancestors came back and visited, along with spirits, fairies, their dead enemies, and every waiter they’d ever stiffed. To ward off these entities, they hollowed out turnips and carved scary faces into them, and they dressed up as animals or demons or Kim Kardashian to trick otherworld visitors into thinking they were also an otherworld resident. They left out offerings of food and drink to appease former enemies who might be bent on revenge. They told stories and tales around bonfires that were meant to keep the evil spirits and darkness at bay. No matter how you cut it, this time of year was scary as hell.

When I was about twelve, my chums decided that trick or treating was for kids and we teens had more mature ways to celebrate Halloween. So on October 31, 1986 I sat in the woods with my friends telling ghost stories. The teller held a flashlight under his chin so as to create a spooky atmosphere and partially blind himself. The bonfire was surely better at keeping the ghouls at bay, because each twig snap made me jolt. And though I heard several creepy tales over the next hour or so, still the scariest part of the evening was knowing that Mr. Benjamin’s full-sized Snickers stock was being depleted without my help.

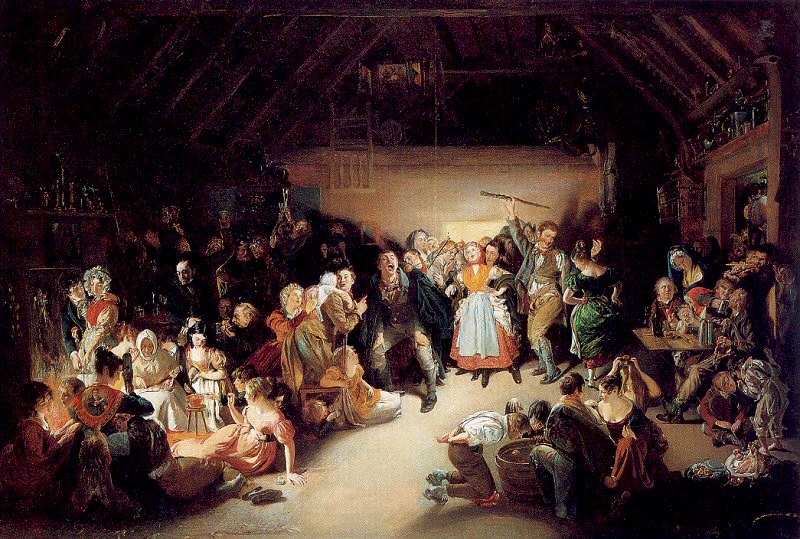

Lots of cultures had their hand in the development of Halloween. The Romans conquered the Celts and brought themes of fruit, blossoming, and sex. The Church came by 400 years later and knocked the sex and the paganism right out of Halloween by adding saints and the pope. From the Church we at least get the name Halloween from All Hallows (saints) Eve. The Irish and the Scottish continued much of the Celts’ original traditions and the Brits get it on the fun in the Britishest way possible by adding arson, hangings, and vandalism. In the American colonies it’s the southern states – Catholic Maryland and Anglican Virginia – where Halloween traditions continue. New England’s puritans would give no quarter to traditions linked to Paganism. A huge surprise, I’m sure. Though the New Englanders wouldn’t allow Halloween, they couldn’t squash what became known as play parties. These were autumnal meetings of farmers, families, and communities who came together to make sugar and sorghum, pare apples, and husk corn. They told stories, ghost tales, had bonfires, and gossiped. The church forbade dancing as a tool of the devil, a restriction which works just as well when applied to rock music and sex. Locals compromised by engaging in square dancing, the lamest of all befooted movements. The Macarena was a few hundred years away, we’ll let them off the hook.

Though these play parties weren’t Halloween parties, they did create an atmosphere ripe for them. So when famine sent Irish and Scottish immigrants over in the mid-19th century, they invigorated Halloween with their carved turnips, costumes, and storytelling. They also brought with them Mischief Night. In the more rural setting of America boys played relatively harmless pranks such as switching cows and putting gates in trees. The less said about the role of the outhouse in these pranks the better. In the 1900s, as people moved from the country to the city, these harmless pranks became harmful vandalism. Broken windows and slashed tires became common on Halloween. Naughty kids in my neighborhood were egging, toilet papering, and soaping homes. I engaged in Hijinx once by stealing a Jack O’Lantern from a neighbor’s trash on November 8th and smashing it against a tree in the woods. Ah, youth.

Halloween has long had a tradition of drinking. The Celts celebrated Samhain over 5-6 days during which they roasted animals and drank beer, wine, and beer they brewed. Archaeologists have found barley at Celtic sites as well as residue of additives like mugwort, carrot seeds or henbane, which would have made it more intoxicating. This also would have helped them deal with unpleasant factoids such as it will be dark for four months, or you are probably going to die in the next four months, or your grandfather’s back from the dead tonight and he wants his pizza stone back. Drinking was part of the British, Irish, and Scottish Halloween parties. The unpleasant development of Mischief Night from harmless pranks into vandalism impels cities in America to begin having citywide Halloween parties and parades. Following in this tradition, in college, Halloween was dedicated to one activity: drinking bad beer in weird clothes.

But the Halloween party really hits its stride in the Victorian era. In the 1870s, magazines in England and America began suggesting tips for Halloween parties, including foods, cocktails, and games. Unlike the spooky themed shindigs we’ve enjoyed with fake webs and black and orange colored sweets, Victorian era Halloween parties centered around games. There were fortune telling and (probably tension-filled) games to see if a lover had been unfaithful. But the overall purpose of these parties seemed to be matchmaking. Hooking up man and woman was the aim of every game and activity, either directly or indirectly. These are too numerous to mention, but they involved peeling apples, setting fires to raisins, fashioning sailboats from walnuts, and women bobbing for apples while men gawked at them and took down names. The Halloween party became so linked to romance people hung mistletoe on October 31. No mistletoe for us, we celebrate with booze.

But what? For centuries, cider has been a preferred autumn drink in Europe and especially in America. So you could go out and get a cider and call it a Halloween. However, one delicious and relatively easy option from the Victorian era is a hot apple toddy.

Hot Apple Toddy

Ingredients

- 5 ounces apple cider

- 1 teaspoon honey

- 2 ounces whiskey or apple brandy (don’t worry…2 ounces to start)

- Lemon wedge, for garnish

- Cinnamon stick, for garnish

- 2 to 3 whole cloves, for garnish

Recipe

Heat up the apple cider at a low-medium heat in a saucepan. While that’s heating up, take a sip of whiskey because it’s dark and scary outside. Next, coat the bottom of an Irish coffee mug or a mug with the honey. Poke the cloves through the lemon slice, and while you are poking take a shot of whiskey, because it’s dark and scary outside. Put the cloved lemon slice in the honey. Add the shot of whiskey (or apply brandy) and then just go ahead and add another. Pour the warm apple cider over top. Take a shot, because it’s dark and scary outside. Stir well. Add more whiskey. If you can still see, drink to the Celts, to full-sized Snickers and the angels that hand them out, and to the end of the time when the light loses and the night wins.