In recent days, research has brought me to the Green Fairy, the Green Demon, Absinthe. When I first moved to the Czech Republic, a wee 2,230 years ago (okay, 2004), Absinthe was on the shelves. There were – and are – shops dedicated to it, at least in order to gain a tourist tromp. It was known to be part of late 19th century Parisian and Bohemian culture and they play on that to get suckers (like me) to buy some strong liquor. Admittedly, it’s not hard.

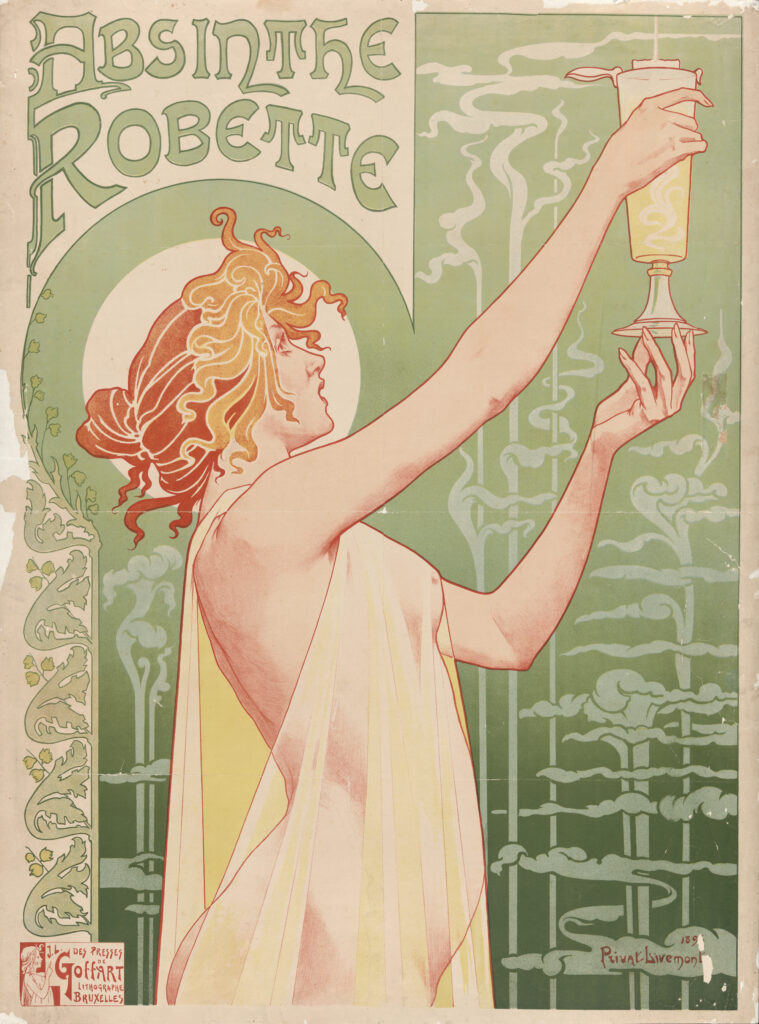

At my going away party at our little corner bar in Pittsburgh, one of my regulars gave me a book all about Absinthe. The book had beautiful pictures of Art Nouveaux green fairies, reservoir glasses, circular tables in dark Parisian cafes and their distant-faced Absinthers. Others showed ghostly humans being visited by the green fairy. Though there is an allure to these paintings, nobody really looks happy. It was 2004, three years after the film Moulin Rouge! gave us a sweaty Ewen McGregor drinking the elixir until Kylie Minogue came out and winked at him, a green, drunk, seductive, sexualized Tinkerbell. On the plane to Prague, I knew I would be trying Absinthe.

It was steeped in booze lore and lots of unverified information was heaved upon it. It’s hallucinogenic, you see a green tint around everything when you drink it. It affected people either phenomenally or adversely, depending on the mood of the storyteller. ‘Kafka drank it all the time, right before he put out the Metamorphoses.” (NB: no, he didn’t) ‘I knew a guy who had to get an intestine replacement after too much Absinthe,” some guy once said. When he was prompted for information, he only muttered ‘wormwood.’

Wormwood became the little-known intoxicant of the hour. No one I knew could clearly define it, as Wikipedia, Smartphones, and ubiquitous Wi-Fi had yet to blast onto the scene making every drunk an immediate on-the-spot smartypants in the field of whatever was being discussed at that exact moment. We just knew what we knew – wormwood made Absinthe strong and hallucinogenic, so much so that it was illegal all over the place. But the fact that we were in Prague made it legal for us. And this made us downright neato.

Making it – and us – all the cooler was the literary and artistic tradition Absinthe carried with it. Van Gogh, Lautrec, Joyce, Gaugin, Rimbaud, Maignan, and Hemingway. All of them visited by the Green Fairy. All undertook L’heure Verte. All considered European artistic geniuses.

Though times have changed and the Czech Republic’s expatriate demographic has changed over the years, back in the early 2000s Prague attracted a very specific expatriate. We had all done something in the field of arts – journalist, graphic artist, playwright. And it was these occupations we offered to our fellow expats at bars, instead of those which had been on our tax returns – bartender, cashier, pizza delivery aficionado. And yet just by buying a ticket to Prague and a sweater with elbow patches, we were now allowed into Bohemian society.

And if you were going to be Bohemian, you had to try Absinthe. We rolled into an Absinthe bar and we went through the whole shebang. The waiter wore a vest. He brought our reservoir glasses and slotted spoons on silver trays. He clearly knew how to wow us wide-eyed expatriates, because that is exactly what we said: wow. I put some Absinthe in my spoon, on which rested a sugar cube. He lit our Absinthe on fire, a thing now which baffles me – why would I drink something into my body that could be set on and stay on fire? I wonder if Van Gogh ever asked himself the same thing.

I blew out the fire and drank it down. Aside from Mezcal, it was the worst thing I ever ingested for a buzz. So I had another. One of the others said there was a yellow haze around everything. Another guy abruptly stood and said he needed to walk around Prague. He left us his wallet, we think, in an attempt to be as ‘Bohemian’ as possible. We were rendered unimpressed by his gesture. I felt very drunk and my throat burned as if I’d been knobbing a cactus. The waiter kicked us out, closing time. We spilled into the street. We felt very Bohemian, so much so that I had to bring myself back down to Earth with a Big Mac.

Though the term ‘Bohemian’ remains an inherent quality that I fully comprehend, it has greatly changed into those things that are profoundly and undivorcibly Czech. It means checkered pants with tearaway calves, dipping rohliky into pink pastika and washing it down with a Branik beer. It’s train station pubs with little groups of blue-overalled construction guys sipping early morning Bozkovs and packing a week’s worth of lunches to bring on your holiday.

Absinthe has been the sufferer of a bad rap. In the late 18th and early 19th century it was blamed for murders and the decay of French society. Across the pond, the British didn’t do much to help Absinthe’s case. They say it as a barrel of high octane, high alcohol problems, and ones they didn’t need. The French had just been beaten in the Franco-Prussian War and were down men. The last thing they needed was Absinthe making more men less capable of defending their borders from – and correctly pegged, it turns out – an aggressive and motivated neighbor.

Much the way that rum was seen as a demon in late 18th century America and Gin Lane was destroying the potential of Brits in the 1600s, France heaved all of its societal woes on Absinthe. It was destroying French society despite the fact that 72% of the drinkership was downing glass after glass of wine. Many countries made it illegal – Belgium, the US, and the Netherlands among them. Though there was a small sect of literati and artists petitioning for the artistic and unique insight that Absinthe’ s green fairy brought out in its drinkers, they were in a minority. Also, they were not doing their cause or themselves any favors by dying of alcoholism.

In the end, Absinthe – the ingredients used by ancient Egyptians and as a malaria-defence by the French in Algeria, was a victim of its own mythology. It would take a barrel of thymine to do what people suggest comes after a glass or two – hallucinations and dropsy insights. But this was no never mind. The Green Fairy isn’t welcome in most societies. And in the Czechs people need to drink it only once to realize that she should just stay in the bottle.