At midnight on January 17, 1920 the Volstead Act made the sale and production of alcohol illegal in the United States. But as Americans had never been good at following rules (or rule for that matter), they almost instantly began finding loopholes and ways to make the inane law obsolete.

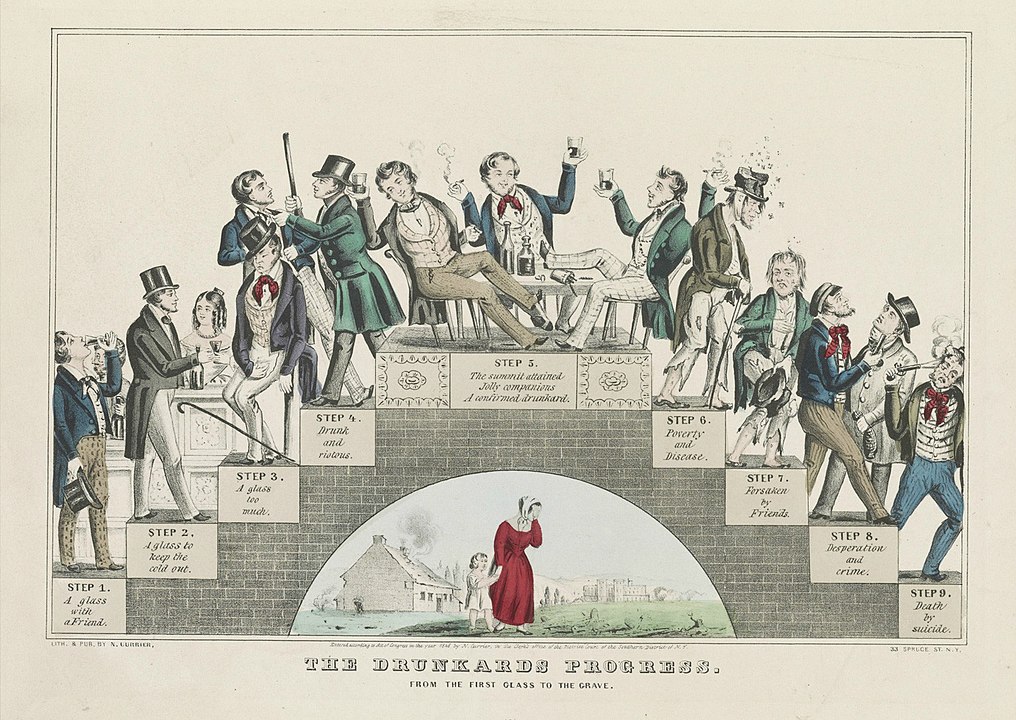

There’s no doubt that Americans had a drinking problem. Thirty seconds after the Mayflower landed on Plymouth Rock, everyone who’d been onboard started scrounging for things to make booze with. The guy who started the first bar was a demigod. Americans drank and tortured witches, the drank and started revolution, they drank and fought each other over slavery. They drank rum, which was cheaper and quicker than beer, and when Irish and Scottish immigrants brought it along, whiskey. America was the drunkest person at the party. Any 19th century attempt to ban alcohol resulted in uprisal and riots.

In the early 20th century, the temperance movement gained some traction. This was a movement led by women, who weren’t allowed in bars (hint hint) and were sick of dealing with drunkard husbands blowing money on booze and ruining their families. The movement was supported by factory owners, who were trying to keep workers sober enough to keep up new working habits (i.e. lots and lots of hours and lots and lots of sadness). Furthermore, prohibition was influenced by good old fashioned American racism. The influx of immigrants between 1880-1920 scared the hell out of a lot of white people, who were nervous that the flood of ‘boisterous’ lower class immigrants and the saloons that kept them happy would lead to a decline in the moral character of America. This, rather than say, slavery. We’ll forgive them this snobbish concern, since they were almost certainly shitfaced when they made it. With a pesky disruption in Europe stirring which would be known as World War I anti-German hysteria blew through the country and the only patriotic thing to do would be to shut down the mostly German-owned breweries.

World War I in itself was another cause of prohibition. Nations tried to ration cereals and grains for the war effort and squash soldier drunkenness. Leaders in Europe had already noted the effects of alcohol on soldier performance, with Kaiser Wilhelm stating that the next war (which would turn out to be WWI) would be won by the least drunk nation. Tsar Nicholas II, whose Russia had lost the Russo-Japanese War partially due to intoxicated troops, banned the sale of vodka in retail stores. The stage was set for booze to be banned, and American went for it.

Almost immediately it became evident that this was the biggest mistake since letting Abe Lincoln go to Ford’s Theater. First off, a huge swath of alcohol-related and peripheral jobs were lost. Not just bartenders and brewers, but waiters, truck drivers, and deliverymen found themselves unemployed. And though many believed that the ban of booze would lead Americans to other pursuits of amusement, they were 100% incorrect. Entertainment such as restaurants and theaters declined dramatically. Americans (correctly) assumed that going to a restaurant or to see a show was no fun when sober, so they just stopped doing it. Prohibition cost the United States over $11 billion in tax revenue and over $300 million to enforce. Like the men they wanted to keep from booze, the Noble Experiment was falling flat on its face.

America didn’t want to enjoy other pursuits, it wanted to enjoy other pursuits drunk – and it would find ways to do that. Americans began immediately exploiting the loophole in the Volstead Act’s wording – which prohibited the ‘sale’ and ‘production’ of alcohol, not the ‘possession’ or ‘ownership’ of it. People took advantage of the opportunity. Pharmacists (whose numbers miraculously tripled) began prescribing whiskey for ailments such as backaches, toothaches, and not wanting to be sober anymore. Religious congregations could buy wine as part of their sacred rites and (surprise) registration in local churches skyrocketed so much that one would think Jesus’ face had been seen in a fajita. Others did it at home with some loopholed help. The American grape industry began selling kits of juice concentrate with explicit warnings that leaving the kit out for too long would result in fermentation into wine. At least they didn’t sell the concentrate with wine glasses or a good camembert. Those who didn’t find loopholes just made alcohol themselves. Moonshine boiled in every basement, garage, and yard. Speakeasies were the worst-kept secret in North America. The cops paid off in booze and cash to keep them that way. “It’s virtually impossible to drink in Detroit,” said one reporter, “unless you walked ten feet and told the busy bartender what you wanted in a voice loud enough for him to hear above the uproar.” The law meant to curtail drinking did nothing less than make Americans experts on how to find booze and, failing that, make it.

What’s perhaps most remarkable is the vast effects that prohibition had on the face of the country, its politics, and the way it drank. The production and smuggling of booze led to a massive rise in organized crime. Names like Al Capone, Arnold Rothstein, and Bugs Moran became infamous. Prohibition’s speakeasies were turning America on to jazz, table service, Italian food, and women drinking in bars. The attempt to strongarm people (read: minorities and poor people) against producing or selling booze mobilized right wing extremist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, who promised to thwart the production of illegal booze and to keep black people from enjoying their lives. It led to the rise in the Democratic Party, as Al Smith ran against Herbert Hoover on a platform against prohibition and against the violent means being used to intimidate lower classes against making alcohol. Though he got beat by Hoover, the next Democrat was a little known guy named Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who ran on a platform of ‘man, who needs a drink?’ Spoiler alert: he won. Three times.

What people drank drastically changed. Before prohibition about 40% of the alcohol drunk in the United States was spirits, but afterwards it soared to 75% as it was the booze most available. Alcohol was smuggled from the United States’ borders – tequila came across at the south, Canadian whiskey from the north. Rum runners brought rum from Cuba and the Caribbean. Bacardi and other rum distilleries ran alcohol vacations in Cuba, where vacationers were met by bartenders at the airport who greeted them with Daiquiris and quickly became the most popular person they’d ever known. Industrial alcohol and unregulated stills were used to make bathtub gin and moonshine. Moonshine was manipulated to make it taste like smoky Scotch (by adding creosote) or bourbon (by adding dead rats or rotten meat). Gin was made by adding juniper oil, water, and glycerine to moonshine. Effective? Probably. Dead rats have always given a heavy, though earthy buzz. However, drinking this cheap booze led to 1000 deaths a year and countless people maimed and blinded.

Because of the clear interest for everyone involved to cover up the taste of awful gin and dead rat bourbon, mixers became the order of the day. Ginger ale (obviously) covered up dead rat taste better than soda, tonic could do a lot to disguise the taste of glycerine and your own impending death. Coca Cola sold by the ton, as people used it as a mixer to alcohol and those who didn’t drink loved it as well. Today we are drinking a cocktail from the prohibition era (don’t worry, no dead rats). We’re drinking the Bee’s Knees.

The Bee’s Knees

Ingredients

- 2 oz Barr Hill Gin

- 3/4 oz fresh lemon juice

- 3/4 oz honey simple syrup 1:1

- Garnish with a lemon twist

Add all ingredients to your shaker except for the garnish. Shake with ice and strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with a lemon twist. The rotten meat has been preadded.